Saturn’s Rings – Last Chance To See

Published:

Originally written for University of Reading Departmental Blog

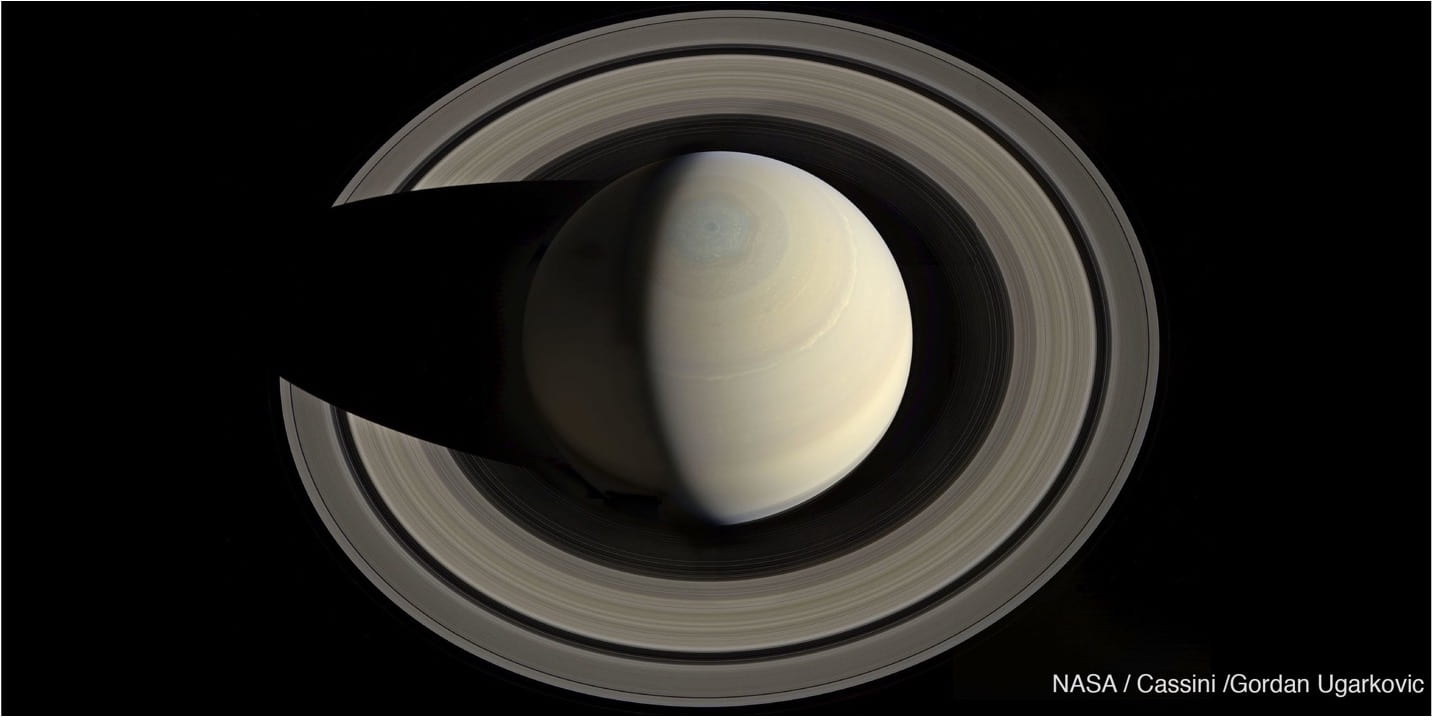

Saturn, owing to its system of rings, is the most recognisable planet in our Solar System. The planet is regularly used in clip-art images alongside a test tube or a DNA strand to represent even science itself. Visible images like that in Figure 1 capture our imaginations, with the rings appearing as a set of countless concentric circles without any obvious signs of disturbance. They seem, along with the planets and moons, to be an eternal piece of the Solar System’s furniture. On closer inspection by the instruments of science, however, we have seen that the rings never ceased to be falling apart ever since their formation. In our own work, we have found that the rings are currently emptying into the planet at a rate of up to 1 Olympic-sized swimming pool every 15 minutes. At that rate, they’d be gone in as little as 100 million years, and while that sounds like an absurdly large number relative to our human experiences, it’s just 2% of the age of the Solar System.

That is just the future of the rings, not the total lifetime; for that, you need to know the age of the rings. If you were to do a Google search for the age of Saturn’s rings today, you’ll find an answer of about 400 million years. The answer returned just over a year ago was 100 million years, and if you look at the results over the past decade, you will see answers ranging from 10 million to 4.4 billion years. That’s about as good as informing us that the rings formed between the creation of the Solar System and up until yesterday. This is no mistake by media outlets; it is because ring-researchers are broadly split into two camps, either the rings are ancient and formed about 4 billion of years ago or they formed on the order of 100 million years ago when the dinosaurs roamed the Earth.

The make-up and movements of the rings offers us some clues as to their origins and evolution. Saturn’s ring system is composed of billions of pieces of icy material in orbit about the planet ranging in size from a grain of sand to bus-sized chunks. Some example orbits are shown in Figure 2: Saturn’s gravitational pull is stronger closer to the planet, so material on the inside track necessarily has to move faster than that of the outside track, in order to prevent it falling in to the planet (more on that later). The rings are mainly made of water in the form of ice with just a trace of dust, itself composed of arrangements of carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen, according to studies of the light spectra leaving the rings (Hedman et al., 2013). If the rings were entirely water, they would appear white.

Historically, scientists thought that the rings formed when a moon strayed too close to Saturn. This beginning has been shelved in contemporary literature, as inward migration was only possible 4.5 billion years ago when circumplanetary gas was present to gas-drag moons toward the planet, and any nascent rings should also have been lost by the same mechanism. Nowadays, we think that the rings likely formed when a watery comet strayed too close to the planet, or a comet struck a moon. When an object strays too close to Saturn, the gravitational force on it is greater on the side facing the planet, so one side of it is pulled away from the other, undermining the object’s own ability to hold itself together. The distance at which disintegration occurs as a result of this imbalance of tidal forces is called the Roche Limit, and material is spread out both toward and away from Saturn, with the former surrendered to the planet, and the latter producing new, small moons just outside Saturn’s rings. The remaining debris is what we call a ring system.

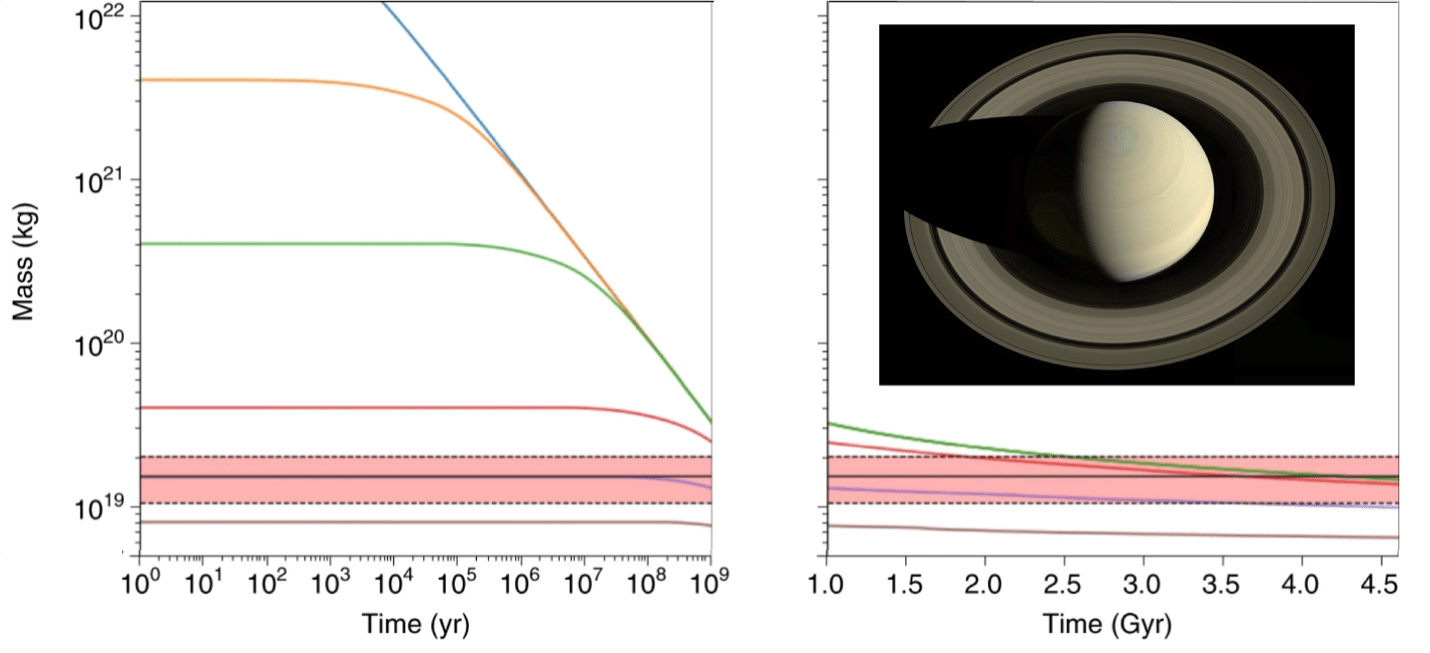

Compelling arguments in favour of ancient rings come from statistics and time-evolution models of ring spreading. If the rings formed from cometary impacts in some way, we require a high frequency of comet impacts, so models point to the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB) as the likely time Saturn’s rings were created, some 3.8 billion years ago. In Figure 3, starting from a particular initial mass, simulations track the mass loss of Saturn’s rings by spreading. The rings could have begun from an arbitrarily large mass and arrived near the present mass estimate of the rings in about 1 billion years; the bigger they were, the harder they fell. So, from a dynamical viewpoint, the rings could have formed billions of years ago, and statistically speaking that was probably during the LHB.

Equally compelling counter-arguments advocate for a young ring age. The rings are pristine, comprised of over 95% water ice, but they are subjected to meteoroid bombardment that, over time, introduces impurities and darkens them, giving them an off-white appearance. Current bombardment estimates imply that the rings are 100 – 400 million years (Kempf et al., 2023), which suggests that a highly improbable event (e.g. an impact), occurred relatively recently and created the rings. On the other hand, it has been argued that impurities may not be deposited as efficiently as we think, with the majority of the material in a dust impact essentially bouncing off the pristine water-ice chunks of Saturn’s rings. Reconciling dynamically old, but young-looking rings is a major challenge today in ring science. If we understand how every piece of the Solar System puzzle got to where it is today, we can help to answer the broader question “where did we come from?”, which is a question humans have asked since we could vocalise it.

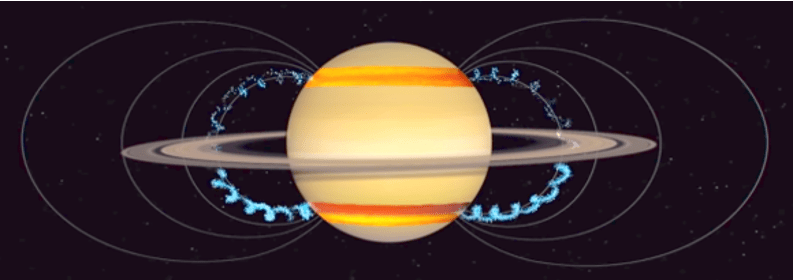

Finding the present-day erosion rate can be used to predict their future life time and give clues to the ring age at the same time. If the rings are being lost quickly today, it’s more likely that they haven’t been around for long. My team’s research tracks a phenomenon known as ‘ring rain’, which involves the flow of electrically charged icy grains from Saturn’s rings to the planet, which travel along the magnetic field lines (O’Donoghue et al., 2019). This enters at the locations shown in Figure 4.

We estimated Saturn’s ring influx from ground-based observations using one of the world’s largest telescopes, the 10-metre Keck telescope, finding that the rings deposit between 0.4 and 3 metric tonnes of material into Saturn every second. If it is constant, as we expect, however, it means that the rings would last “only” a further 100 to 1100 million years from today. Crucially, this mass loss is not yet included in simulations like that in Figure 3. If it were included, each curve would be steeper at every point, as the rings would be disappearing as they spread out in addition to raining into the planet. This alone implies that the rings may be on the younger side, but the range of ring rain erosion we have derived so far is admittedly wide, owing to the faintness of ring rain’s emission as seen from Earth.

Our future observations are aimed at establishing how fast the rings are presently dying with much lower uncertainties, helping to predict the ring’s future lifetime and to better constrain when they were first formed. These may be with the Keck telescope, which has just had an upgrade to the instruments we use, or with the more sensitive James Webb Space Telescope. For now, we know that Saturn’s rings at least aren’t forever, they are more like transient debris fields, rather than permanent fixtures. If Saturn’s ring system is short lived and formed while the dinosaurs roamed the Earth, we are very lucky to be alive at a time when they are present. If they only last a further 100 million years, you might want to go out and enjoy them while you still can.

References

Hedman, M.M., Nicholson, P.D., Cuzzi, J.N., Clark, R.N., Filacchione, G., Capaccioni, F., Ciarniello, M. Connections between spectra and structure in Saturn’s main rings based on Cassini VIMS data. Icarus 223 (1), 105–130, 2013.

Crida, A., Sebastien Charnoz, Hsiang-Wen Hsu, and Luke Dones. Are Saturn’s rings actually young? Nature Astronomy, 3:967–970, 2019.

O’Donoghue, J Luke Moore, Jack Connerney, Henrik Melin, Tom S. Stallard, Steve Miller, and Kevin H. Baines. Observations of the chemical and thermal response of ’ring rain’ on Saturn’s ionosphere. Icarus, 322:251–260, 2019.

Kempf, S., Nicolas Altobelli, Jurgen Schmidt, Jeffrey N. Cuzzi, Paul R. Estrada, and Ralf Srama. Micrometeoroid infall onto Saturn’s rings constrains their age to no more than a few hundred million years. Science Advances, 9(19):eadf8537, 2023.